History on the Land – Part Two

By Samantha Ford, Owner of Turn Stone Research

Editor’s Note: Read Part One of this series, focusing on the Nye family’s time at NBNC from 1792 through the 1840s, here.

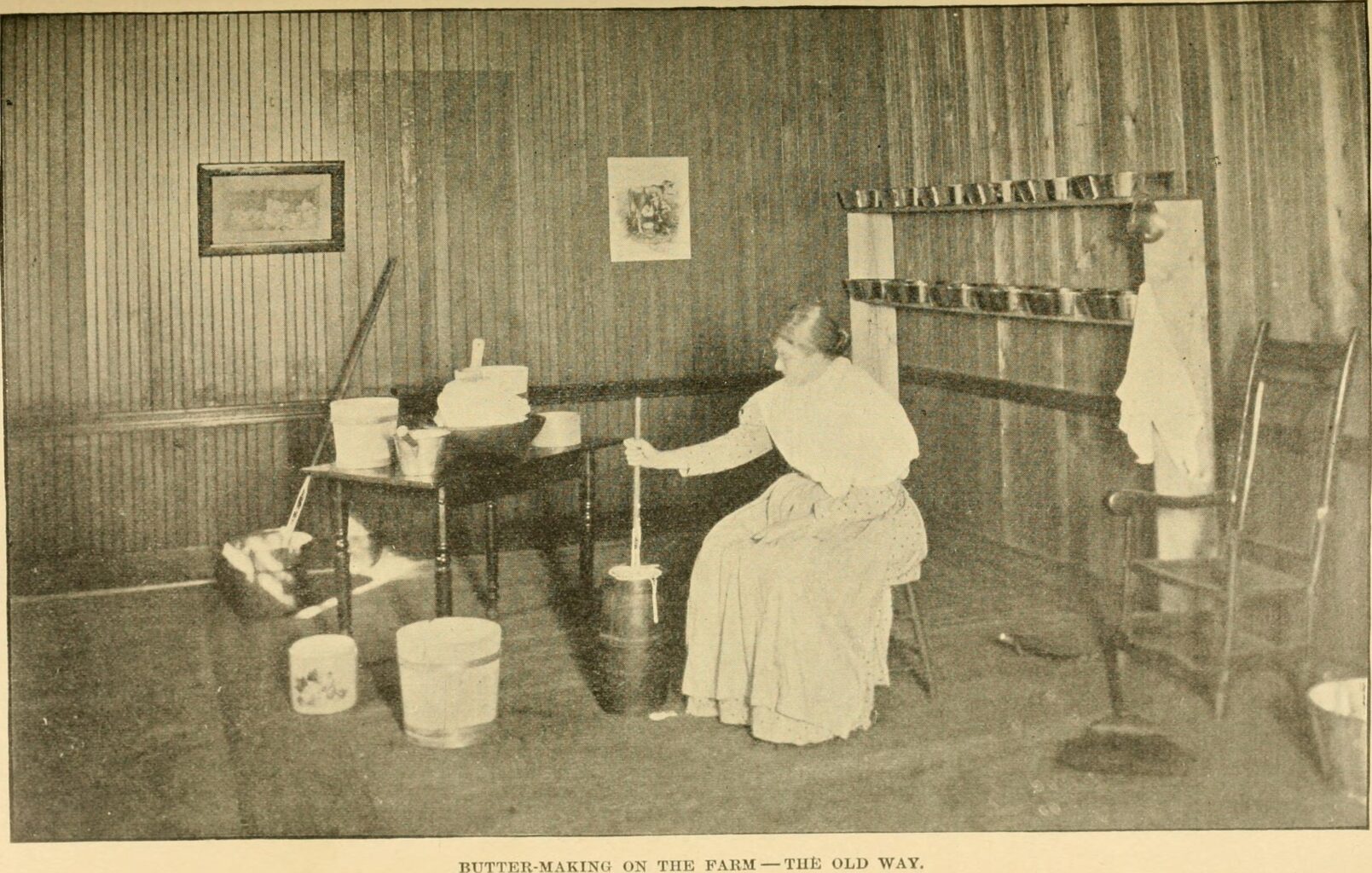

The first chapter of the North Branch Nature Center farmhouse story ended in the 1830s, when the Nye family built the current farmhouse after a fire destroyed the original 1790s house. Evidence of this fire remains on the charred floor joists in the basement, which were likely reused from the original house. From the 1830s to the 1860s, the farm was a small subsistence operation of around 120 acres, spanning both sides of Elm Street (see map below). The 1860 Agricultural Census gives us the first glimpse of this typical small family farm: 85 acres were cultivated with 45 tons of hay, 380 bushels of oats, 50 bushels of corn, and 150 bushels of potatoes harvested. The livestock included three horses, one pig, and three cows that produced 200 pounds of butter.

A year later, in 1861, Charles Calkins of Massachusetts purchased the property from the Nyes. Charles was a wealthy doctor from the Boston area who spent the next few years purchasing neighboring tracts of land. By 1864 the farm was enlarged to 206 acres, and the holdings included several of the neighboring farmhouses (some are still extant). At the next Agricultural Census in 1870 the production of the Calkins farm had increased significantly to 200 acres in active crop production, resulting in 60 tons of hay, 350 bushels of oats, 100 bushels of corn, and 200 bushels of potatoes. The livestock increased to four horses, 16 cows producing 250 pounds of butter, and 10 sheep that produced 50 pounds of wool. The addition of sheep reflects a shrewd business decision to diversify farm products and a potential response to the call to help supply the Union Army with wool for their uniforms during the Civil War. However, the Calkins family member responsible for these improvements was not Charles, but his wife Susan.

In the 1800s the property, outlined in red, spanned both sides of Elm Street and extended across the river.

In 1869, Susan Calkins was finally granted a rare divorce from her husband, after years of public scandal over his mingling with younger women. It’s clear Susan preferred the relative quiet of their country farm, far from her husband’s reputation in Boston, and she was awarded the property in the divorce settlement. At the time it was worth around $15,000, no small value for a divorced single woman to own in her own right. The deed contains some highly unique language awarding Susan full rights to her property, “for her sole and separate use and free from the interference or control of her husband.” Susan was also awarded an additional $5,000 value from their personal estate containing “all the livestock, horses, hay, grain, farming utensils, tools and household furniture in and about the farm and buildings in the town of Montpelier.”

Susan chose to remain in Montpelier after the divorce and continued to oversee the farm operations through a farm manager. The extent of her holdings can be better appreciated on the 1873 Beers Atlas of Montpelier. Her name “Mrs. S. M. Calkins” appears above four separate houses that were part of her 206-acre farm. A neighbor, Edward Irish, likely worked as the farm manager and listed Susan as a “Boarder” on the 1870 Census. At the time it would have been considered uncouth for a single woman to reside alone, and so her reputation was preserved by appearing as a boarder when in reality she owned the majority of the surrounding land and was listed as the sole owner on the 1870 Agricultural Census. It’s clear Susan’s divorced status was not a liability as she remained single and accepted by her community for the rest of her life. In the newspapers she was even described as a “widow” (with the quotation marks). This mark of respect was one clearly earned, and a rare example of the time.