2021 Saw-whet Season Wrap-up

By Gavin Young, owl banding assistant and U-32 High School senior

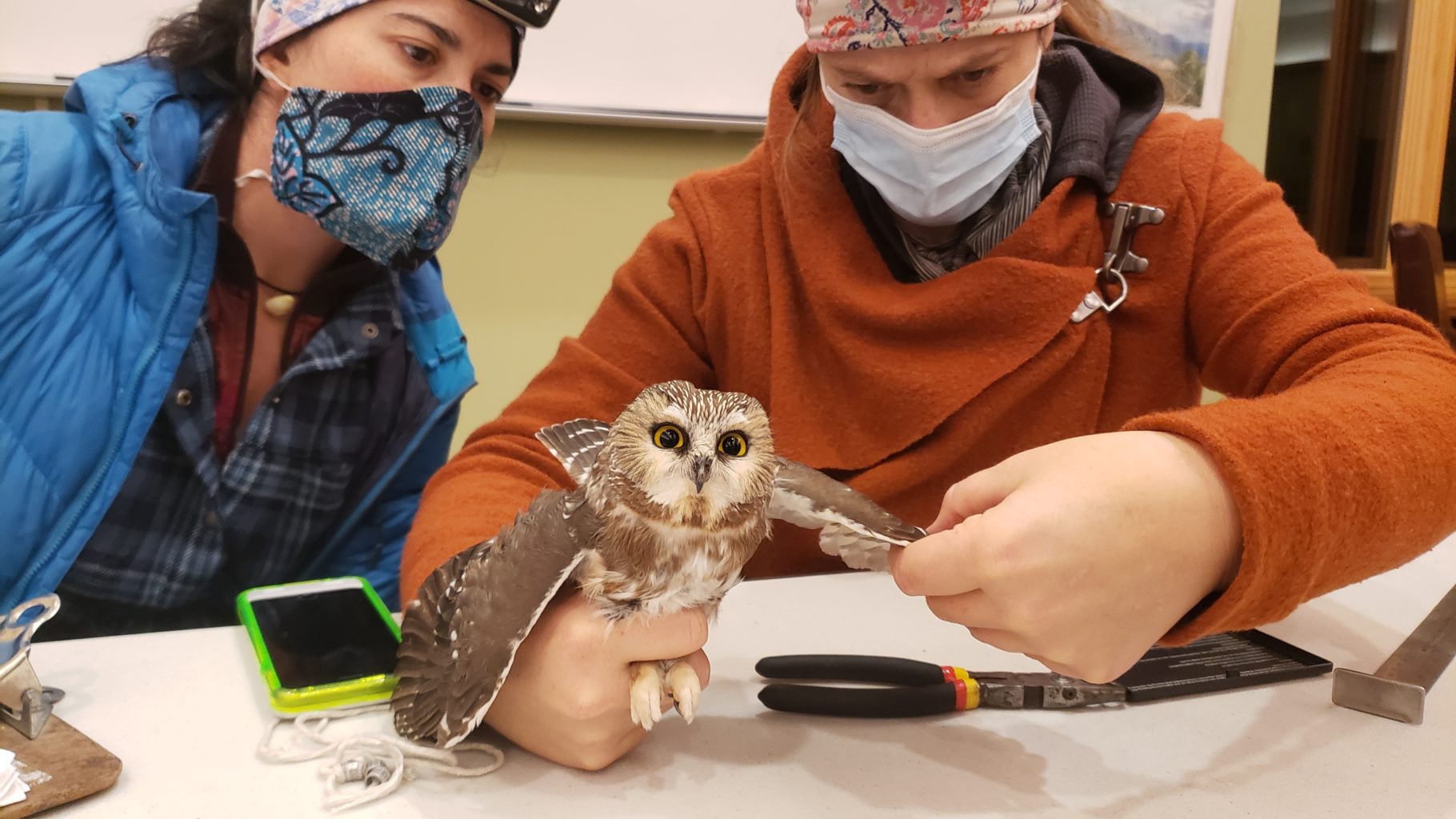

The month of October is the time to band Vermont's smallest owl! As the Northern Saw-whet Owl is migrating south for the winter, Central Vermont and the North Branch corridor see a flush of these birds move through the area. Facing dark and cold nights, NBNC staff and volunteers actively netted, banded, and released 123 different owls this year. Don’t fret: when an owl is banded, the bird is only in our possession for a short amount of time. We collect data, apply a small aluminum band, and let the owl fly away within minutes.

Owl Seventy-eight and male/female ratios.

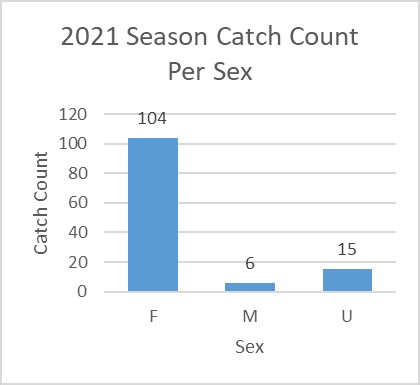

NBNC was out every night setting up mist nets and playing an audio lure to attract as many Saw-whet Owls as possible. While all the data we collect is valuable, the owls most valuable are those with bands already on them! This year we had 9 recaptures, including one owl that was recaptured three times! This bird’s last two numbers of its band serial number are 78, So that's what we’ll call her. Seventy-eight was netted and banded at NBNC on October 11th 2021. At this time, she weighed 100 grams and had a wing chord of 147 millimeters, her large size identifying her as a female. The sex ratio of banded Saw-whet Owls at NBNC since we began banding in 2013 has been 83% female, 4% male, and 13% unknown. Over the years we have banded over 700 Saw-whet Owls and these sex ratios have stayed steady. One hypothesis as to why we catch more females is because our loud audio lure broadcasts the male song, thereby either preferentially attracting females or repelling males. As far as we know, the sex ratio of Saw-whets encountered passively in the wild is 50/50%.

Seventy-eight was caught again in the same net a week later on the 19th, weighing 96 grams, and then recaptured yet again on the 1st of November weighing 92.9 grams. This multiple-recapture scenario is highly unusual in saw-whet owl banding. Less than 5% of banded owls are ever seen again.

It’s possible that all the recapturing, along with many environmental factors, stopped her from migrating farther. Her apparent weight loss could have been either from her paused migration due to foul weather, stress from her time at the banding station, or simply because we caught her on an empty versus a full stomach.

Annual Capture Rate Fluctuations

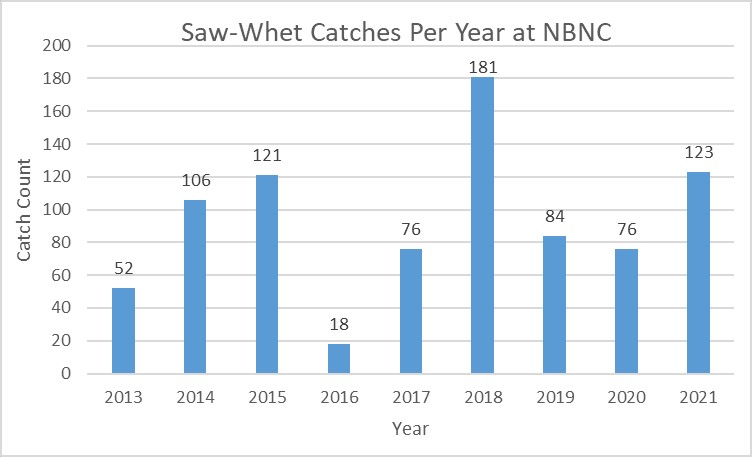

This year we had the second highest catch count for all nine years that NBNC has participated in saw-whet banding. The peak was in 2018 when 181 Saw-whets were banded. The long term fluctuation in our data does not allow us to make an estimate of population decline or increase, but it still tells us something interesting about the Saw-whets we catch. The data we collect gives us some direct information about the species, and raises multiple questions to explore about the natural history of Saw-whets.

On the graph above, we find short term fluctuations caused by an ecological factor. The large spike in 2018 that followed the 2016-2017 dip in catches may be because of the natural shifts in the seed yield of spruce and fir trees. A “masting year” is when a tree produces a huge number of seeds compared to other years, which is followed by a dip in production the following year when the tree's reserves are exhausted. The flush of seeds in a masting year will produce more seeds than seed-eaters like rodents and finches could ever eat in a season, allowing the uneaten seeds to germinate. These masting years cause a feast for the Saw-whets primary source of food: voles.

As the 2-to-6-year cyclic masting of conifer trees in the north affects the population of a species like the red backed vole, we can track the entire effect of the ecological cycle through the capture rate of Saw-whets. In other words, a surplus of seeds causes a surging vole population, which causes a boom year for the Saw-whet Owls, and higher catch counts at NBNC.

Aging Saw-whets

We can tell the age of the owl by the molt pattern on their flight feathers. New feathers will fluoresce pink under a blacklight because of the organic compound porphyrin. This compound degrades over time and with exposure to daylight, allowing us to see which feathers are old and which are new by how much they fluoresce. The specific patterns of new and old feathers determine the age of the owl, like hatch year owls with their new feathers and bright UV wardrobe.

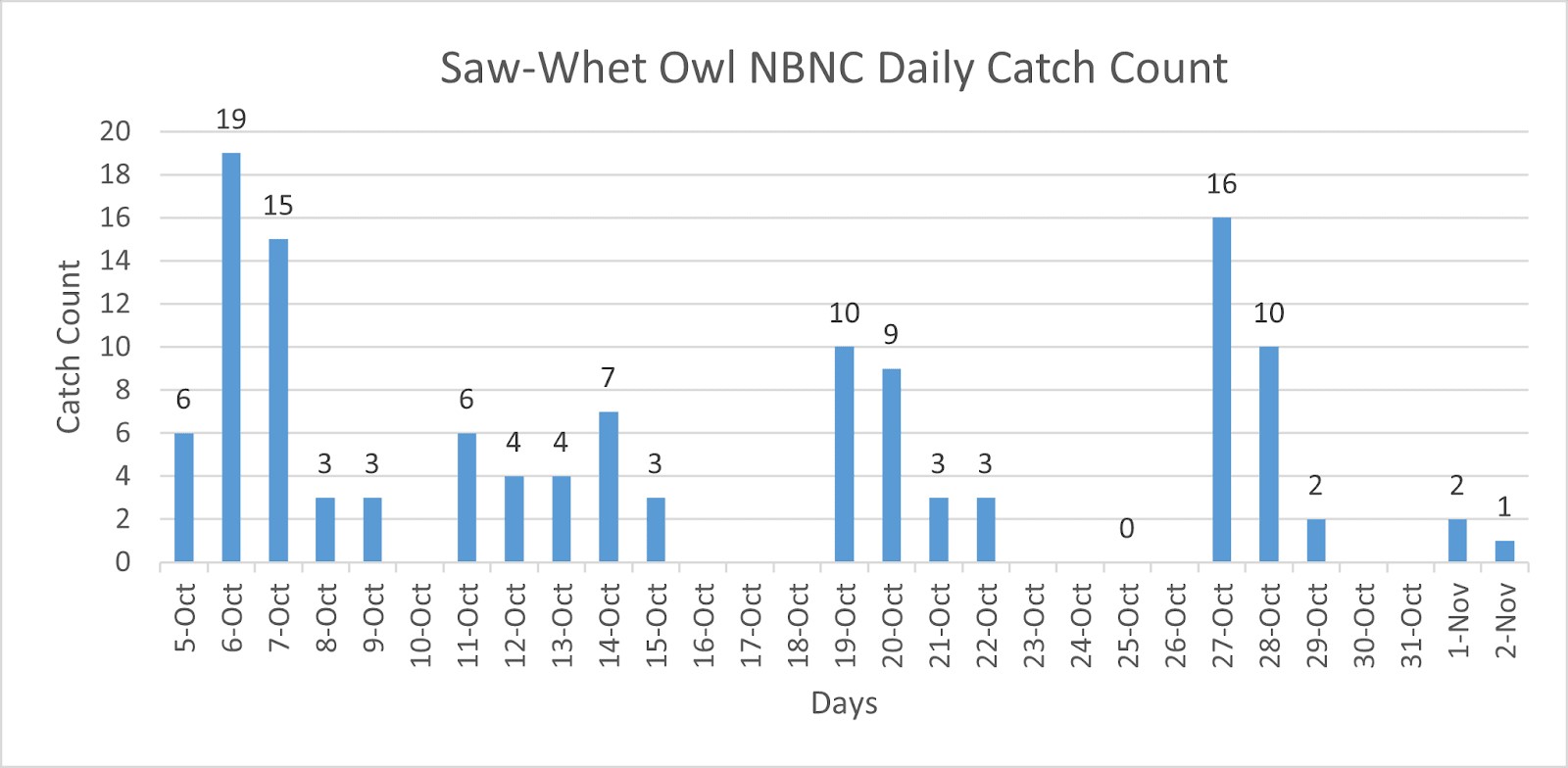

Nightly capture rates and possible explanations

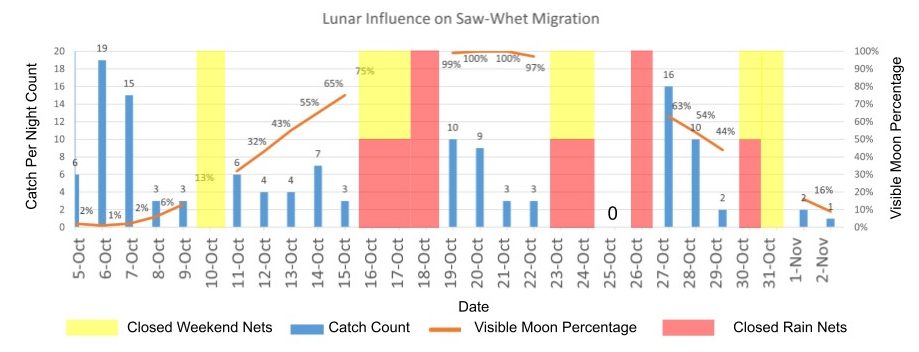

One of the clearest factors that affects our Saw-whet nightly catch count is the rain. Saw-whets will not move around on nights with significant precipitation. This October had 14 rainy days. Note: when looking at the graph, note that we do not open nets on rainy nights because Saw-whets would not be moving in those conditions. Nets were also closed on most weekend days. Rain on the 23rd - 26th likely created a buildup of Saw-whets waiting to migrate south and we caught an unusually high number of owls (16) the next clear day on the 27th.

There is another hypothesis that we can explore to explain the late season spike on the 27th. For four days (19th-22nd) the moon was above 97% full. The lunar cycle greatly impacts the migration of some birds. Saw-whets’ nocturnal nature allows them to forage in the dark, but the increase in moonlight changes their foraging behavior. Increased illumination increases predator avoidance by their rodent prey. Meanwhile, the Saw-whets themselves become more vulnerable to predators like Barred Owls.

Looking at the graph above, the lunar cycle is tracked by the orange hyperbola. The breaks in the hyperbola are rainy nights or weekends when we were not banding. The yellow represents weekends, the red shows rainy nights, and rainy weekends are shown by bars with both colors. What can this graph tell us?

- We have high catch counts when there is less moonlight.

- We still catch some owls during the full moon, showing that owls are still in the area.

- There was no rain during full moon days so weather was not a confounding factor.

- The decrease we see during the full moon and the high count rates on both sides of it suggests that the full moon decreases Saw-Whet movement.

Why then, during the height of the full moon, were there so many owls caught on the 19th and 20th? The first two days of 97% and greater illumination followed three consecutive days of rain. This may have forced the saw-whets to be more active than they would otherwise be during a bright moon phase.

The other important factor for Saw-whet migration is wind and temperature. Cold nights with a breeze blowing from the north tends to yield high numbers of owls. The two highest capture nights this season both had favorable wind directions, as did the 19th and 20th, when we caught a relatively high number of owls during an otherwise unfavorable moon phase.

Visitors to the Saw-whet Station

We’d like to say a huge thank you to all our lead banders, our banding apprentices, and our banding assistants for enduring a long month of cold nights and sharp talons. We’d also like to extend our gratitude to the 180 visitors who came to the banding station this year during our public demonstrations, our NBNC members’ nights, or those who simply dropped by the station on a clear, crisp night. While our research contributes valuable information to our understanding of this seldom-seen species, NBNC also deeply values the opportunity to share these wild owls with our community. These feathered conservation ambassadors change lives when put in the hands of children and adults alike, and we are grateful to be able to facilitate these experiences.

Finally, we’d like to say thank you to the owls, for putting up with a modicum of unpleasantness during their fall migration, which we hope will be greatly outweighed by the contribution of their data to science, and the tremendous impact on the people whose lives they touch.