The Nature Of: Owls on the Move

By Zac Cota, AmeriCorps Teacher-Naturalist

Article from the winter edition of our “Field Marks” newsletter

A constant “toot”echoes across North Branch’s star-lit field: the call of the Northern Saw-whet Owl. This one’s not an actual owl, but an audio lure used to attract these robin-sized predators. Throughout October and November, our bird-banding station is reconfigured to catch Saw-whets, the smallest of Vermont’s ten regularly documented owl species. Hundreds of thousands of Saw-whets migrate south each autumn, and while some stay to tough out Vermont’s winters, others fly as far south as Georgia.

Across their range, researchers wait patiently through the long autumn nights, checking their nets at regular intervals. Once caught, each bird is fitted with a small metal band bearing a unique serial number. Banding allows scientists to study migration patterns and population dynamics across the continent. Previously considered threatened and extremely rare in many states, researchers discovered that the Saw-whet is actually one of our most common avian predators — they’re just experts at staying out of sight.

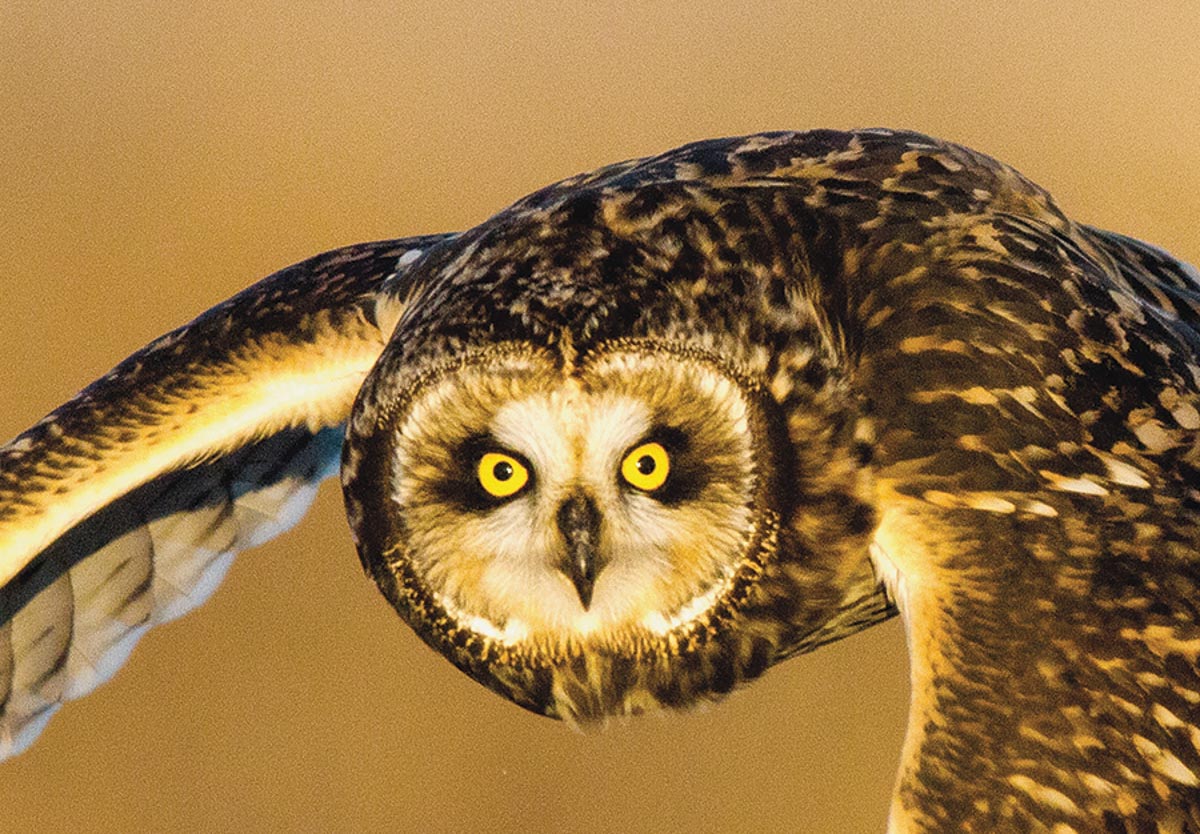

Saw-whets aren’t the only owls journeying through Vermont. In November and early December, Short-eared Owls move south to spend the winter searching for rodents in extensive open areas. These highly specialized owls live mainly in open grasslands and tundra, and are one of only a few owl species to nest directly on the ground. Three times the size of a Saw-whet, the Short-eared Owl’s mottled brown and tan pattern has a subtle beauty. Both owl species dine on small rodents, but the Saw-whet ambushes prey from deep within interior forests, while the Short-eared Owl patrols the open fields on long, broad wings. Their gentle, moth-like flight draws human admirers to migration stopover sites like the Dead Creek Wildlife Management Area in Addison.

(Photo: Short-eared Owl in flight. Photo by Jim Sullivan)